Here is a shout out to my PhD student Sean Liew, whose paper recently came out in J. Org. Chem. Sean has been with us for about 2 years and, among other things, developed a great way to make vicinal diamines. One of the key control elements in this chemistry is attributed to the dimeric nature of aziridine aldehydes we have been working on. Below you see the transformation I refer to as well as Sean himself. Plus, I am showing a model Sean developed that accurately predicts the observed selectivity. The central feature of this chemistry is the hemiaminal that keeps the two monomers glued to each other for the duration of the transformation. The way the process operates is like this: the dimer partially dissociates, which allows it to interact with the incoming nucleophile. The said nucleophile is delivered to the nearby electrophile. In the present embodiment, we have boronate playing the role of the nucleophile and iminium ion acting as the electrophile. Towards the end of the reaction, the aziridine hemiaminal dissociates, releasing the product plus the monomer, which redimerizes. This is how we think about this chemistry. We are now trying to apply Sean’s reaction in a variety of contexts and the prospects are encouraging. Sean and I were asked by the J. Org. Chem. to come up with artwork so that the paper gets featured on the cover of the journal, which is cool. I am happy for Sean, although the deadline for the cover art is upon us. Why don’t I send Sean an annoying reminder email right about now?…

Author Archives: ayudin2013

Soakers

Below is the structure of Fxr1. It is a methyl lysine-binding domain of human mental retardation-related protein 1, which is an important target. While I was in Russia (back as of yesterday), Elena emailed me with the good news that we now have Fxr1 crystals. We need them for co-crystallization/soaking experiments. Unfortunately, the quality of these crystals is not high and we have to continue our efforts to optimize these crystals. I hope this is something my graduate student Victoria will be able to do at some point…

Right now I want to make a distinction between co-crystallization and soaking of crystals. Co-crystallization is when we attempt to crystallize a protein along with its small molecule binder. If anything, this can actually help us in the case of Fxr1 (above) as there is a chance that the molecules we designed will improve the crystal quality. On the other hand, soaking is when you already have good quality protein crystals and place them into a solution of a small molecule. The idea is that a small molecule diffuses into the lattice and “gets stuck” in places that are not random. This is a blueprint for the discovery of new probes for proteins that have no cognate ligands.

Tomorrow is the day when I am going to “cross the Rubicon”: we intend to run soaking experiments together with Dr. Aman Iqbal. Aman is an expert in soaking, having arrived to SGC from Astex in Boston. Recently, Aman managed to get a co-crystal for one of our joint targets. Tomorrow is the time to soak another one of our target proteins in cocktails of small molecules. We intend to produce around 80 crystals and analyze them by X-ray crystallography to find binders. While I was away in Russia, Conor, Rebecca and Shinya worked hard and made a library of structurally advanced fragments. In addition, we got some really cool compounds from Prof. Laurel Schafer (UBC) and her Ph.D. student, Andrey Borzenko (by FedEx earlier today). I hope we will collaborate with more people who have nice heterocycles and are keen to understand how they interact with complex protein targets. I am particularly hoping to have something interesting going with Laurel’s nice molecules. I will blog about her methods at some point. I think it is fair to say that our heterocycle-related methodology these days It is geared towards filling the holes on protein surfaces. This is fun.

At the end, I just can’t help but recall that nice paper by Fujita in Nature (http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v495/n7442/full/nature11990.html). In it, he describes what is effectively an inorganic analog of the 3D protein lattice/small molecule soaking experiment. The paper is awesome, but I just caught myself thinking that a version of this method has been among protein scientists’ tricks for a while. I refer to soaking, of course…

Ring economy

One area of heterocycle chemistry that interests me the most is related to ring expansion and ring contraction reactions. What can be better than taking an existing ring and converting it into a new one, with different connectivity, yet mostly containing the original atoms? I think we should call this strategy “ring economy”… Just joking (I am poking at atom economy, and the like). Ring expansion processes relate to my lab’s interests in cyclic peptide expansion (which I hope to disclose soon). Speaking of small unsaturated heterocycles, I always pay attention to any reaction that allows one to transform existing molecules into larger rings. Smaller are fine too (contractions). Invariably, the mechanisms are complex and demanding because one needs to get used to the idea of disrupting an aromatic ring, followed by breaking the core, making space for new atoms, and restoring the order. A telling example is, for instance, the good old Ciamcian-Dennstedt rearrangement shown below:

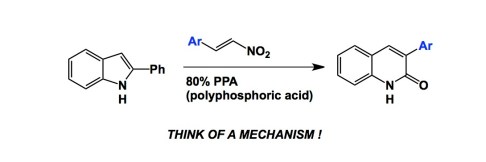

The dichlorocarbene is generated from chloroform. It then acts on pyrrole and, voila, you have a one-step route to the pyridine ring. These kinds of reactions are powerful, yet there is not too many of them. While attending the Heterocycle conference here in Russia, I learned about a new addition to this class of reactions. It was described in Professor Aksenov’s presentation. Incidentally, he is the organizer of this conference and I have to admit that I have not met anyone else who has so many jokes up his sleeve. Aksenov’s lab has been active in the utilization of polyphosphoric acid, which deserves another post one day. I still can’s wrap my head around how versatile this reagent is. Here is a representative ring-expansion example and a link to the corresponding ChemComm article:

http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2013/cc/c3cc45696j#!divAbstract

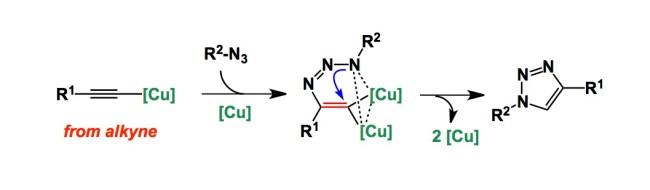

On copper, click chemistry, and our craft

I am still in Pyatigorsk. Valery Fokin, one of the founders of click chemistry gave a talk earlier today. In it, Valery shared the results of a mechanistic investigation aimed at understanding the inner workings of the copper-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition between azides and alkynes, one of the workhorses of bioorthogonal chemistry. The Cliff notes summary of his study is shown below. We need to think about two distinctly different roles of copper here. One is to make the terminal copper acetylide, whereas the other one – to recruit the azide. Together, the two conspire to fuse the 5-membered ring.

Valery’s recent Science paper is the account you may want to look at:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/340/6131/457.abstract

The methodology used to collect some very complex kinetic data is what interested me the most. Microcalorimetry was used, which is a method that enables one to follow step-wise changes in enthalpy as the reaction progresses. Donna Blackmond has done some nice foundational work in this area.

At the end of the day we retreated to the hotel and had some wine and whiskey with Valery. It was great to see my dad join the conversation. He is a physicist by training and some of the comments he made were thought-provoking. For instance, he noted that it is just astounding how many different, substrate-dependent reaction conditions we deal with. For him seeing all our tricks involving some random combinations of additives is mind-boggling. He thinks that the fact that no one has systematized and created a fractal-based approach to handling complexity in chemistry is just insane. Indeed, chemistry is odd in that regard and appears to be so much more empirical than pretty much any other branch of science. This is why comparing it to what happened to quantum mechanics during the last century (when Einstein just saw it all and went after his unifying theories) is a stretch. But who knows. Maybe there will be someone like Mendeleev in the future who will make sense of it all and will create some multi-dimensional system for reactions. I doubt it, though. I think chemistry will remain more of a witch’s brew…

In the south of Russia

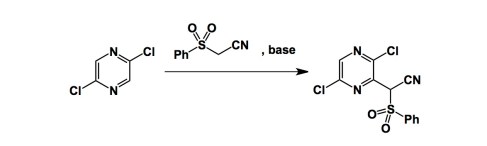

I have been silent for a bit, but that is because of travelling… I am literally 150 miles from Sochi (the host of Winter Olympics), if I can get over the Caucausus mountains that is. I am at a small town called Pyatigorsk in southern Russia, which is where my father is from. That is a rare coincidence. In fact, he decided to join me on this trip. A conference is dedicated to the chemistry of heterocycles and is taking place here in Pyatigorsk. I am enjoying every moment of it, having already learnt a ton of new stuff. Vladimir Gevorgyan gave his usual fireworks type of a lecture, which was awesome. I must admit that I was really intrigued by the talk given by Prof. Makosza from Poland. He is an elderly gentleman speaking in a rather unassuming way. The next thing you realize is that you have the father of phase-transfer catalysis in front of you! The latter is well familiar to many people by now, but I was particularly intrigued by his foray into vicarious nucleophilic aromatic substitution. I do think (and many people would agree, I am sure) that this area has been unjustly overlooked by many of us. Take a look at the following example, by the way. Could you have anticipated this outcome? I can’t say that I could.

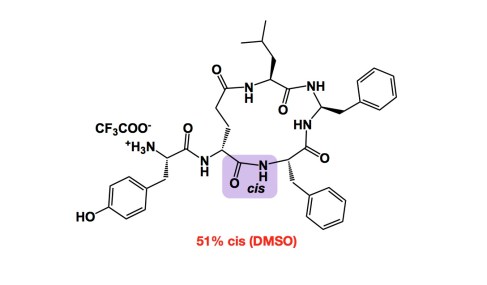

cis-Amide bonds

While it is easy to control cis- vs trans- double bonds in Wittig reactions (think about stabilized vs non-stabilized ylides), it is certainly not the case with amide bonds. In fact, one of the fascinating questions I like to think about together with my students is why we are always tempted to draw trans-amides as products of amide bond forming reactions. Granted, trans isomers are more stable. But who’s to say that they always form under kinetic control? This is a mystery… One might say that this is not one of those “relevant” mysteries as in linear peptides cis amides will certainly (and rapidly) isomerize… But hold on a second: this does not need to happen in cyclic variants. I give you a very informative example from the late Prof. Goodman. This aminal-containing macrocycle contains one amide bond that is largely cis in solution. The reason this is cool is that this case is not based on proline, which tends to give a large proportion of cis-amides for different reasons. We need to think more about deliberate control of cis/trans isomers in these systems.

The honour roll: Prof. Hideki Sakurai

Please indulge me for one more fluorine-related post (I don’t know what’s happening to me) but I promise that I will leave the subject for a while. This is not about some late-breaking news or anything like that. It isn’t even about a paper that is particularly useful in the eyes of a modern function- and goal-oriented chemist. This work is not even new, but it is what we should all care about: it is thought-provoking. This paper was submitted to JACS by Prof. Sakurai almost 20 years ago. It details a molecule that was dubbed by the authors as a “merry-go-round” kind. You can see it in the graphic below. At first glance, its silicon NMR spectrum should contain a doublet. But it ain’t. There is a triplet and the reason for that is that the fluxional behavior around C-Si bonds leads to a unique situation in which each silicon is hexavalent, yet neutral! And then the most interesting thing happens: at higher temperatures Si NMR is actually a septet. The reason: degenerate fluorine migration (hence the name “merry-go-round”) such that each Si “sees” six fluorines at a time.

Hey – no one blogged in the days of Prof. Sakurai’s paper, so I will do it. Incidentally, this was one of the works I fell in love with while doing my PhD with Prakash and Olah. I think we can all name a few papers we remember from a while back. Some of them do leave a lasting impression.

Concluding the trip at SFU

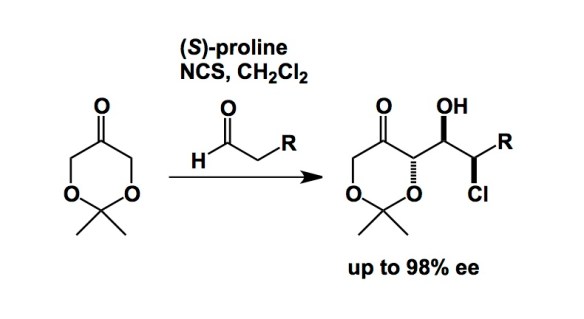

I did not know there are so many black bears here in BC… I can’t say that I saw one, but the stories I heard from Rob Britton earlier today were fabulous. Rob was the host during my visit to SFU, which is located in Burnaby, about a 30-minute ride from Vancouver. Rob’s work in the area of chloroaldehydes has been of particular interest to me. The chemoselectivity of this process is notable, given what’s brewing in the reaction mixture (I refer to NCS and proline co-existance). His lab has put this process to some great use in natural product synthesis.

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/ol401370b

While there were no bears in sight, our dinner with Rob Britton and Bob Young (a former VP of Chemistry at Merck-Frosst, now a Professor at SFU) in Deep Cove, North Vancouver, was a great conclusion to the scientific part of the trip…

Fluorine in Vancouver

I had a great time at UBC yesterday. Amongst other science stories in my talk I described how we make crystals of peptides at SGC. Somehow this really got the graduate students interested. They peppered me with questions, which was fun.

This visit was a chance for me to see some old friends and meet new people. I would like to say my special thanks to Jen Love, who invited me and organized my visit. Throughout the day, there was a certain “fluorine” theme I could not help but notice. Dave Perrin, who is always passionate about science told me about some of his lab’s work that has convinced the world about how specific activity of radiolabelled trifluoroborates is to be understood. I encouraged you to read this scholarly work:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201208551/abstract

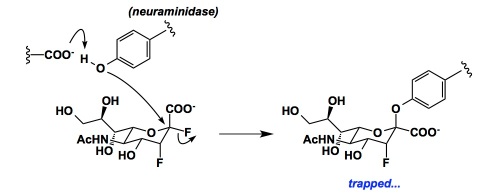

Steve Withers described a great story related to his neuraminidase inhibitors. Although I saw his paper in Science not too long ago, I was thrilled to hear the story from the man himself. Each of the fluorines is critical to the behaviour of this intriguing inhibitor (below) and the work is a testament to the fine balance of relative rates that is possible through the careful selection of substituents.

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/340/6128/71.abstract

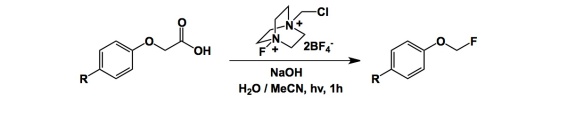

Glenn Sammis concluded the triumvirate of fluorine-related vignettes for me and showcased how his lab (in collaboration with J. –F. Paquin) managed to get radical fluorination to go:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201206352/suppinfo

I also had a great time with Marco Ciufolini, Jen Love, and Laurel Schafer. I have followed their work for a number of years and will dedicate a special section some time in the near future. My former student Taka is in Marco’s lab. It was great to see him (good luck with the total synthesis, Taka!).

Victoria – the gem of the West Coast

I started my three-day West Coast trip today. The first stop was at the University of Victoria. I have to say that Victoria is probably the most beautiful place I have been to and I have been to many… The town is right on the Pacific Ocean coast and is a short 15 minute flight from Vancouver. The harbor somehow reminded me of Copenhagen, but it is better.

I gave a talk at the Chemistry Department here, spreading my lab’s gospel of amphoteric reactivity. Most importantly, I got to meet some of the folks whose work I have known for a number of years, and also made some new acquaintances. Fraser Hof’s work in interrogating methyllysine binding domains is really exciting, I can’t wait to read about the latest findings his lab made in recent moths. My graduate student Rebecca Courtemanche hails from Fraser’s lab and I gave Rebecca a big shout out in my talk. Robin Hicks told me about his lab’s research on redox-active ligands based on indigo. Indigo! This is the stuff the jeans are coloured with! Really creative stuff. Who would have thought that this old dye holds so many surprises. I also met Jeremy Wulff, one of UVic’s youngest faculty members. His lab does so many interesting things. I think that his cyclic peptide work geared towards interrogating a protein/protein interface mediated by two beta sheets is very thought-provoking. I am looking forward to seeing some time soon in the literature.

A recent paper in Angewandte by Neil Burford really caught me by surprise, I must say. Neil told me about this piece in detail. We all know that palladium does reductive elimination really well, which is the basis of the vast majority of cross-couplings. But what about reductive elimination from a main group element? I was not aware that this is possible. Yet, Burford’s lab showed that reductive elimination happens in a very curious fashion from antimony compounds. I wonder if main group elements will one day be shown to display this kind of behavior in catalytic reactions…

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201210012/abstract