I think all students in sciences rightfully ask questions about their future employment. We live in uncertain times and job prospects are of great concern to our students. I still remember 1997 when I was a PDF at Scripps. My friends all thought I was a complete fool to go into academia. They kept saying: “rather than doing something so crazy, you need to think about what’s more or less guaranteed for life, Andrei”… They referred to jobs at Pfizer, Merck, etc. Of course you know what happened then. The ground rule that governs capitalism is the bottom line. Accordingly, it became profitable for big corporations to outsource production and, later, discovery, to places like China and India. People started losing their jobs in North America and it has been tough here for several years. But guess what? The pendulum eventually swings back. The same laws that governed leakage of jobs to Asia must eventually move to equalize the costs here and there. You might still say that the difference in costs remains large and will continue to stay that way for a while. Well then… I give you widespread corruption in places like China. We are all aware of some serious issues that keep popping up these days, all pointing to fraudulent practices in the pharmaceutical R and D in China. Several big companies are now implicated in scandals and we can foresee a situation when it becomes too risky to do business there. It is always that good old risk/benefit analysis. The jobs may then very well come back to North America. Check out the following high profile report published in Science:

Author Archives: ayudin2013

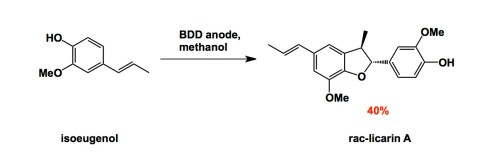

Boron-doped diamonds and just good old platinum

Electrosynthesis is one of my long-time passions, although my lab has not done it recently (but we shall…). I nonetheless pay attention to novel materials that people start to use these days. Here is one: boron-doped diamond. This material has been known to inorganic chemists, but recently the group of Nishiyama in Japan showed that anodic oxidation on the surface of boron-doped diamond leads to very effective formation of methoxy radicals. Learning from this fairly simple case, the authors expanded the method to the synthesis of a natural product, licarin.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201200878/abstract

I am curious if this and other unusual electrode materials will find new applications in selective oxidation.

Keep in mind that there is, of course, reduction accompanying any electrochemical oxidation. Protons typically get reduced to hydrogen gas on platinum. People rarely draw this reaction, though (it is assumed). Another thing to remember is that ANODE is where oxidation takes place, whereas CATHODE is for reduction. That’s a simple rule to keep in mind.

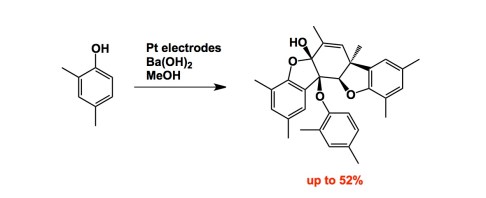

Since we are on the subject of oxidation, let’s increase complexity a bit… Here is Siegfrid Waldvogel’s excellent recent contribution to organic electrosynthesis. A good cumulative exam question, I must say! The increase in 3D complexity achieved in this synthesis is staggering:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201006637/abstract

A tribute to the Greeks

Many of the molecules studied in our lab at the University of Toronto belong to the amphoteric class (hence, the title of this blog). Amphoteric molecules contain counterintuitive combinations of functional groups that are expected to react with each other, yet don’t do it prematurely due to a good kinetic reason (this is case-dependent). Not long ago I caught myself thinking that we do not put things into proper perspective and rarely trace the origins of the idea to its humble beginnings. To do that, we have to go back to the Greek philosophers and, in particular, Heraclitus, the father of dialectics. Here is his paraphrased quote:

I think we can all name a couple of examples from the literature that use this concept metaphorically. One of my favourite books, Bulgakov’s “Master and Margarita”, hinges on the idea that good and evil can’t live without each other (i.e. they need each other because neither can exist without a contrast). In our case things are much more benign – a nucleophile and electrophile that co-exist… But still…

Sticking with arginine

When asked: “What is the pKa of benzylamine?”, one of my postdoc friends from the old days with Barry Sharpless at Scripps would strike back: “In which solvent?”. This is a great way to buy time, I suppose, while being a bit of a smart ass. I have found this answer to be somewhat irritating but, if you think about it, it is also true that context is everything…

Below you see arginine. No one (in a million years) would suspect arginine to be a hydrophobic amino acid. This label would go against intuition that comes naturally to a chemist. Yet, hydrophobicity is also context-dependent. As a matter of fact, arginine is a residue par excellence in terms of stacking with aromatic groups, thereby plugging all sorts of hydrophobic pockets. Here is a view from a crystal structure Elena and I solved recently. You see how arginine’s guanidine group is perfectly positioned inside one of the aromatic cages that makes this particular protein special. We want to interrogate the pocket, yet it is filled. Arginine – please go away, darn it! We need our fragments there, not you…

Reaching across big rings

Those of us who care about cyclic peptides eventually come to grips with the idea that, despite their relative strength, amide bonds can be fragile when placed within constrained environments. This is the reason why cyclic tripeptides are inherently unstable. The proximity of amide bonds accounts for the transannular reactivity shown below (left). While this sort of reactivity is certainly undesired if one wants to have access to a 9-membered ring composed of amide bonds, it also provides enabling opportunities in synthesis. I can name a couple of examples right here. The first one comes courtesy of Phil Baran (http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja2047232), and showcases how a 9-membered ring collapses in the course of palau’amine synthesis. The second one is a nice example from Dirk Trauner’s lab (http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/v3/n7/abs/nchem.1072.html). In this case, loline synthesis was shown to proceed through nitrogen attack at the intermediate bromonium ion. These examples prove that powerful reactions can be designed with transannular reactivity in mind. Unfortunately, these cases further underscore the notion that the majority of medium ring amides are not to be associated with stability…

Do not underwrap your hydrogen bonds

It is hard to wrap one’s head around the concept of underwrapping (no pun intended) but it is not so intimidating (underwrap = expose to solvent). Ariel Fernandez uses it to describe peptide structures. He applies a variety of metrics to arrange the corresponding peptide molecules on the spectrum of toxicity (and many other properties such as cell permeability). In his Nature Biotechnology commentary several years ago, Ariel has made some compelling arguments pointing to a correlation between properties such as toxicity of a peptide and the extent of hydrogen bond accessibility. There are many other properties described in this work as well.

http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v22/n9/full/nbt0904-1081.html

For instance, the worst wrapper of hydrogen bonds in the entire protein database is the peptide toxin isolated from green mamba venom.

Given the amount of current interest in macrocycles made out of amino acids, people should pay special attention to how hydrogen bonds are “shielded”… A molecule must also keep its hydrogen bonds dry if it wants to cross the cell membrane. This is another lesson emerging from Ariel’s work.

On how far and how fast things go

I fell prey to the dictum I preach in my classes… I often say something along the lines of: “Chemistry is more or less about how far a system can go and how fast it can do it. In our craft we ought to control both”. Of course, I refer to the thermodynamic / kinetic control. I wonder how many students have heard me say it over the years and got fed up hearing it…

The image above is not an exoplanet or our Earth’s moon viewed from some haystack. It is a photo of an exciting macrocycle which has, as you can see, crystallized. The crystals emerged as a result of a painful process that involved me setting up 1056 experiments. What you see is an expanded view of our typical 3mm-in-diameter well. The most frustrating thing is that these crystals, albeit needle-like and imperfect, vanished within 24 hours. It is interesting that the crystals formed fast (kinetics were favorable), but eventually disappeared due to their instability. Fortunately, we do have the Le Chatelier principle in our disposal and my next steps will be to repeat the experiment and preclude the reverse from happening. Since this is a vapour diffusion-type method (with water ruling the gas phase), I will need to carefully play tricks with the other reservoir. This is a very precious molecule, though. All 0.02mgs of it. Stay tuned.

A bottle of wine and some memories…

Here is a lovely bottle of wine I had not long ago together with my good friend and colleague Mark Lautens. The bottle is from 1986 and has waited for us in Mark’s impressive wine cellar. I was not even an undergrad at that time! Gorbachev was still in power, I lived in the Soviet Union, and my generation had no clue what awaited us in about 4 years. I knew I wanted to be a chemistry teacher but I was not really sure I would get into the University.

Anyways, we always have fun when we visit Mark’s place. It is too bad Jovana (my lovely wife) was on call that night and could not join us…

Speaking of Mark Lautens – here is a really cool paper from his lab from a while back. The reason this work is special for me is that it deals with amphoteric reactivity. In this particular case, Stéphane Ouellet (one of Mark’s PhD students at the time) showed how vinyl epoxides behave as amphoteric reagents.

I love the tautomerization event that creates the nucleophile capable of aldol chemistry!

Methylene taken away: norcysteine

Today I want to talk about norcysteine, an unnatural analog of cysteine that has the methylene group “taken away”. That’s right.

You look at norcysteine and you go “How in the world is this stable?”. But apparently it is stable… Jean Rivier of the Salk Institute in La Jolla has done really nice work that demonstrates some of the unusual properties of this amino acid. Here is a representative paper:

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ol0606740

You might imagine that the corresponding SS bonds would be really different (shorter or longer SS bond?) from typical Cys-Cys connections. The thing for me is that the aldehyde oxidation state of the alpha-carbon might not mesh well with a reasonable expectation for configurational stability of this particular amino acid. However, norcysteine-containing peptides are configurationally stable at the alpha methine position. One can imagine a ton of applications for this molecule. I doubt we will see a variant of the native chemical ligation, but who knows?

Old (and new) stomping grounds

I feel that ever since I started my position here in Toronto in 1998, we have consistently encountered more or less the same core challenge (despite covering a wide palette of research areas). I refer to our never-ending pursuit of molecules we a priori attribute some value to. It all started with our interest in fluorinated BINOLs, which were initially really hard to make, but then my students mastered this class of compounds and developed some really nice applications. I also recall how we started with aziridines. It was Shadi Dalili (now teaching at UT Scarborough), who started working with cyclohexene imine. Iain Watson joined the project shortly thereafter and really taught us how to handle these sorts of material. Nowadays we deal with macrocycles, which are really tough both synthetically and from the standpoint of NMR characterization. But we are learning and are making progress. Still, it is always one kind of central molecule (or scaffold) we get transfixed by and put a ton of effort before learning how to deal with it. I tip my hat off to my students who keep passing this torch of hard-target search for things that are tough to make.

On the subject of the old stomping grounds… An old friend, Cathy Crudden (Professor at Queens U.: http://www.cruddengroup.com), came by today with her student Lacey Reid. Cathy met me at MaRS where I currently work (my SGC sabbatical…), we had a nice lunch (next one on me, Cathy!) and chatted about some heavily fluorinated biaryls. This discussion brought to memory my lab’s first inroads into fluorinated BINOLs. We eventually mastered them and I just want to share what was the origin. Here is it:

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ol991244v

You see – we first wondered about the relative reactivity of benzyne vs tetrafluorobenzyne. The latter turned out to be way more stable and, consequently, less reactive. But it has been useful for us. We employed it in order to run Diels-Alder reactions with 3-methoxythiophene, which then led us to fluorinated BINOLs. I still see my man Subramanian Pandiaraju (my first PDF), who spearheaded this effort (he is now with Ontario Institute of Cancer Research) and we reminisce of the old days. Fundamental reactivity has always been central to us. At the end of the day, what we really care about is how molecules react with each other.