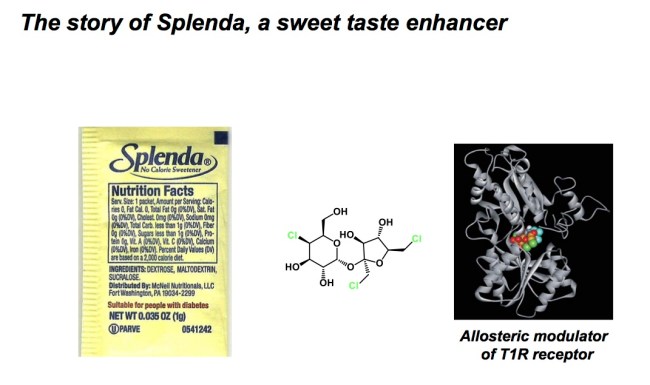

Here is one of my favourite subjects: electrophiles. They are often used as reactive intermediates in synthesis, which is common knowledge. The vast majority of electrophiles are toxic to humans for a very clear reason: our bodies are largely composed of nucleophiles. Indeed, it is difficult to name an amino acid residue in our proteins that is electrophilic in nature. Apart from the ones that are neutral (leucine, alanine and the like), amino acids are nucleophilic (cysteine, arginine, lysine, serine, etc). Therefore, one should expect irreversible reactivity between exogenous electrophilic species and proteins. In fact, there are many drugs that act by way of covalent modification of the nucleophiles found at protein active sites. We are also told (rather emphatically, in all sorts of MSDS sheets we get from Aldrich!) to avoid contact with electrophilic chemicals. Alkyl halides are on top of some of those lists and many of these chemicals are banned by the Montreal Convention. It may come as a surprise, therefore, that some odd balls pop up here and there and, on the surface, there is no explanation for their relatively benign nature. Take Splenda as an example. This artificial sweetener contains sucralose, whose structure is shown below. This stuff is served at Starbucks, not to mention a ton of other establishments. One look at this molecule was enough to make me cringe when I first saw it. I instinctively considered all of my cysteines as potential targets! However, sucralose is benign and does not covalently inactivate cysteines. In fact, it is an alosteric modulator of T1R receptor, which explains its effect as a sweet taste-enhancing additive. There was a great PNAS paper on that some years ago (see the link below).

There is another lesson in this story and it relates to the foundation of Sn2 chemistry, the rate of which is rather sensitive to steric bulk around the reactive site. This is why we teach our students that neopentyl systems are lousy electrophiles. So, there you have it, folks: Splenda is quite ok for you despite the chloromethylene and chloromethyl groups in it. Next time you put it in your coffee, rest assured that your cysteines will remain intact due to relative rates and the good old physical organic chemistry.